Analysis of Martian soil by NASA's ongoing Mars Curiosity rover turned up a surprising amount of water, as well as a chemical that will make a search for life more complicated, scientists said on Thursday.

A scoop of fine-grained sand collected by the rover shortly after its August 2012 touchdown showed the soil contains about 2 percent of water by weight.

"It was kind of a surprise to us," said Curiosity scientist Laurie Leshin with Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

"If you take a cubic foot of that soil you can basically get two pints of water out it," she said. "The soil on the surface is really a little like a sponge for sucking stuff out of the atmosphere."

Scientists announced last week that so far the planet's atmosphere shows no signs of methane, a gas which on Earth is strongly tied to life. Plumes of methane had been detected over the past decade by Mars orbiters and ground-based telescopes.

Methane, which should last about 200 years under Martian photochemistry, also can be produced by geologic events.

The water was found by heating a tiny bit of soil to 1,535 degrees Fahrenheit (835 degrees Celsius) inside Curiosity's chemistry laboratory and analyzing the resulting gas releases.

Scientists found that in addition to water, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide and other materials, the sands of Mars also contain reactive chemicals known as perchlorates.

NASA's now-defunct Phoenix lander had found perchlorate in the planet's northern polar region, but scientists did not know until Curiosity's analysis that the chemical apparently is widespread.

"They seem to accumulate on the surface (of Mars), almost like snow," said lead Curiosity scientist John Grotzinger with the California Institute of Technology.

That is important to know because looking for organic material on Mars may now require a new approach.

"The tried-and-true technique on Earth is to heat the sample and take a look at the gases that are produced," Grotzinger told Reuters.

But the heat can cause perchlorate to break down, in the process degrading the organic compounds scientists are looking for, Grotzinger said.

"We as a community will have to wrestle with understanding the behavior of perchlorate," he added.

The presence of perchlorate in soil samples could explain why scientists have so far had a hard time finding organic material on Mars. Even if life never evolved on Mars, the planet should have organic carbon deposits left by crashing asteroids and meteors, scientists believe.

The results of Curiosity's first 100 days on Mars, published in the journal Science this week, also revealed the presence of a rock with a far more complicated chemical history than scientists expected to find on Mars.

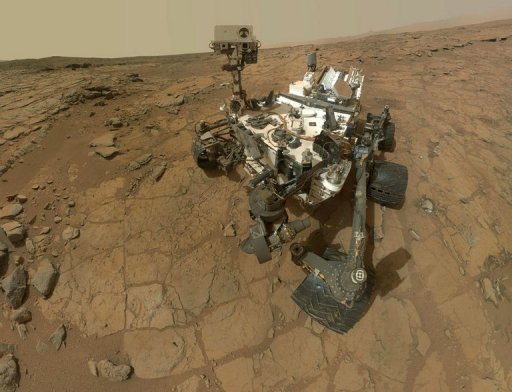

Curiosity is continuing its search for habitats that could have supported ancient microbial life. It already has found one suitable location inside an ancient slab of bedrock near the rover's Gale Crater landing site.

Curiosity is driving to its primary science site, a three-mile-tall (5-km) mountain rising from the crater's floor.