The men with no legs did not surprise me.

When I first traveled to Vietnam fifteen years ago, as a journalist covering a U.S. charity that distributed used wheelchairs, I was not surprised to meet young farmers who had been maimed in peacetime by the explosion of old bombs, America’s wartime litter.

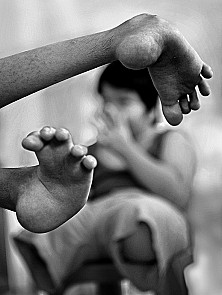

The deformities, however, were much more common than I expected, and more troubling. In Ho Chi Minh City, Nha Trang, Da Nang and Hue, we saw dozens of children and young adults with physical and mental disabilities, often both.

These unfortunate souls, we were told, suffered birth defects resulting from the toxic defoliant Agent Orange that was sprayed by the U.S. military over vast areas of Vietnam.

I did not doubt this, but did not take it as gospel. Birth defects can happen for many reasons. For all the anecdotal evidence, establishing causal links to Agent Orange (AO) or any substance can be tricky, not unlike diving the proof-positive cause of a cancer cluster. In contrast, there is nothing ambiguous when old bombs blow up.

But time keeps reinforcing the case against AO as a kind of slow-motion war crime – albeit accidental, insofar in the sense that the perpetrators did not appreciate the true, insidious menace of this form of chemical warfare.

Vietnamese authorities say that perhaps one million Vietnamese have been harmed by AO in ways large and small.

The latest bit of evidence comes in a new study at the Columbia University School of Public Health which concluded that, from 1971 to 1982, U.S. Air Force reservists who flew in and maintained 34 aircraft that had been previously used to spray AO in Vietnam were found to be exposed to greater levels of dioxin that were earlier acknowledged by the Air Force and the U.S. Veterans Administration. After any years without monitoring, tests revealed the lingering presence of dioxin in the aircraft, of which only three remain, the others having been smelted in 2009.

"These findings are important because they describe a previously unrecognized source of exposure to dioxin that has health significance to those who engaged in the transport work using these aircraft," said environmental engineer Peter A. Lurker, the lead investigator of the study published in the journal Environmental Research.

The results underscore, once more, the stubborn resilience of dioxin – and how that undercuts the stubborn habit of denial by U.S. government authorities. There is some sad irony that just as the Vietnamese have no choice but to live with the toxic legacy, so the U.S. military took the problem home with them.

So hundreds if not thousands of Americans, it seems, may have been victimized by AO simply by occupying these aircraft. This could lead to healthcare benefits and monetary compensation for individuals who have developed ailments that, under U.S. law, are considered positively linked to exposure to Agent Orange.

But what does it mean for millions of Vietnamese who are said to have suffered, many tragically, because of the long-term effects of dioxin contamination? Not much. There is little comfort in another footnote of the hypocrisy of U.S. policy regarding the legacy of what the Vietnamese call the American War.

Early on, U.S. military authorities were dismissive of the human risk posed by what it called Operation Ranch Hand, the mass spraying designed to defoliate the jungle that hid their enemy.

After the war, as U.S. veterans developed a variety of dread diseases, suspicion about the herbicides grew. Eventually, sympathy for veterans led Congress to adopt a law that presumes that the millions of U.S. servicemen who served in Vietnam were exposed to Agent Orange, making them eligible for certain veteran's benefits if they develop any number of conditions that range from severe acne to dread cancers and ischemic heart disease.

Billions of dollars worth of health and disability benefits related to AO have been disbursed.

Meanwhile, the official U.S. posture regarding AO in Vietnam is underwhelming, even though the contamination is widespread and persistent. While it is true that the U.S. has in recent years been spending millions to clean up and neutralize dioxin hot spots in Da Nang and other former staging areas – work that should have been started 20 years ago, when the nations normalized relations. Instead, the poison was allowed to fester and inflict harm.

But most of the aid that directly addresses the impact on families and individuals comes from philanthropic organizations such as the Ford Foundation and charities, many backed by U.S veterans, such as that wheelchair charity, fifteen years ago.