ANCHORAGE, Alaska -- Earth’s ice is melting faster today than in the mid-1990s, new research suggests, as climate change nudges global temperatures ever higher.

Altogether, an estimated 28 trillion metric tons of ice have melted away from the world’s sea ice, ice sheets and glaciers since the mid-1990s. Annually, the melt rate is now about 57 percent faster than it was three decades ago, scientists report in a study published Monday in the journal The Cryosphere.

“It was a surprise to see such a large increase in just 30 years,” said co-author Thomas Slater, a glaciologist at Leeds University in Britain.

While the situation is clear to those depending on mountain glaciers for drinking water, or relying on winter sea ice to protect coastal homes from storms, the world’s ice melt has begun to grab attention far from frozen regions, Slater noted.

|

|

| An aerial view of floating ice taken by a drone launched from Greenpeace's Arctic Sunrise ship in the Arctic Ocean, September 15, 2020. Photo: Reuters |

Aside from being captivated by the beauty of polar regions, “people do recognize that, although the ice is far away, the effects of the melting will be felt by them,” he said.

The melting of land ice – on Antarctica, Greenland and mountain glaciers – added enough water to the ocean during the three-decade time period to raise the average global sea level by 3.5 centimeters. Ice loss from mountain glaciers accounted for 22 percent of the annual ice loss totals, which is noteworthy considering it accounts for only about 1 percent of all land ice atop land, Slater said.

Across the Arctic, sea ice is also shrinking to new summertime lows. Last year saw the second-lowest sea ice extent in more than 40 years of satellite monitoring. As sea ice vanishes, it exposes dark water which absorbs solar radiation, rather than reflecting it back out of the atmosphere. This phenomenon, known as Arctic amplification, boosts regional temperatures even further.

|

|

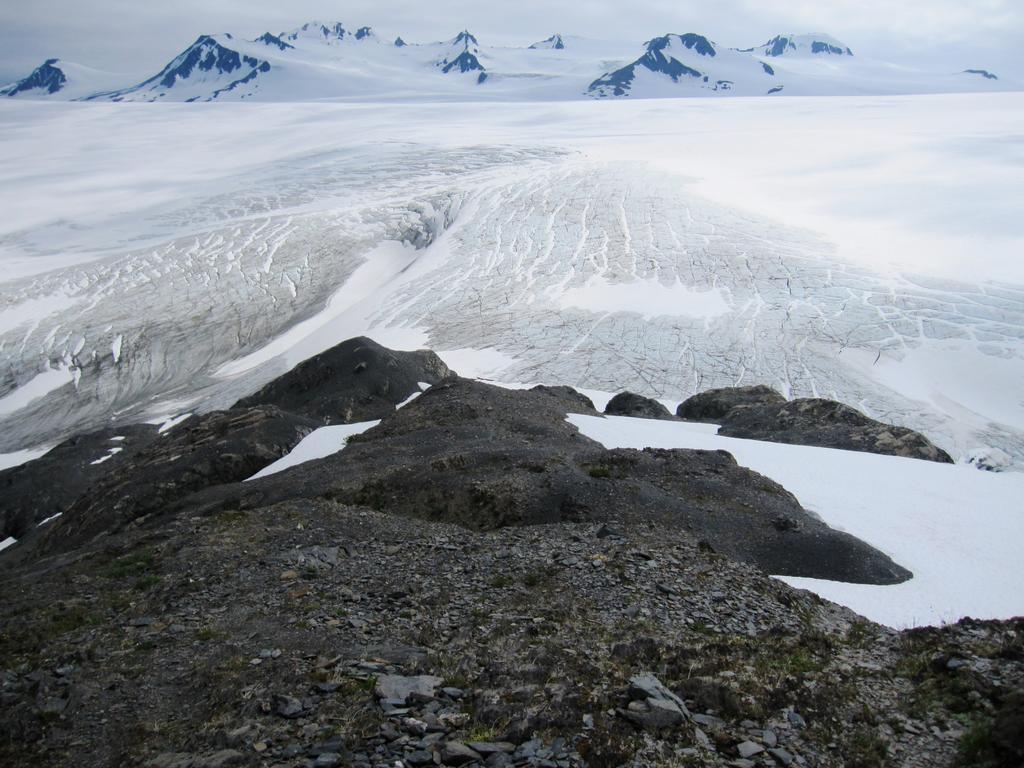

| Portage Glacier as seen from Portage Pass in Chugach National Forest in Alaska, U.S. July 7, 2020. Photo: Reuters |

The global atmospheric temperature has risen by about 1.1 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times. But in the Arctic, the warming rate has been more than twice the global average in the last 30 years.

Using 1994–2017 satellite data, site measurements and some computer simulations, the team of British scientists calculated that the world was losing an average of 0.8 trillion metric tons of ice per year in the 1990s, but about 1.2 trillion metric tons annually in recent years.

Calculating even an estimated ice loss total from the world’s glaciers, ice sheets and polar seas is “a really interesting approach, and one that’s actually quite needed,” said geologist Gabriel Wolken with the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys. Wolken was a co-author on the 2020 Arctic Report Card released in December, but was not involved with the new study.

|

|

| Harding Icefield in Kenai Fjords National Park, Alaska, U.S. July 15, 2017. Photo: Reuters |

In Alaska, people are “keenly aware” of glacial ice loss, Wolken said. “You can see the changes with the human eye.”

Research scientist Julienne Stroeve of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado noted the study had not included snow cover over land, “which also has a strong albedo feedback”, referring to a measure of how reflective a surface is.

The research also did not consider river or lake ice or permafrost, except to say that “these elements of the cryosphere have also experienced considerable change over recent decades.”

|

|

| A view of Utqiagvik, formerly known as Barrow, Alaska, U.S. on October 4, 2018, with no sea ice on the horizon and North Slope Borough crews working to protect the shoreline from storm surges. Photo: Reuters |