Making anime is an intriguing, time-consuming and heavily labor-dependent process. As part of learning and writing this series of articles, I’ve relied on information supplied by some artists and production house leaders, my own research and general information from media sources. Anime in Vietnam is poorly documented in English and there was a lot of translation involved.

I used a questionnaire to solicit personal observations from professionals working in the Industry. I didn’t get many responses but I’ve included comments from Vu Pham, the founder of Rainstorm Film Studio, which has produced architectural, advertising and general animations since 2007. Le Vinh (real name withheld by request), a 3D animator from Ho Chi Minh City, and Nguyen Xuan Hien, who works for MPNavi in Ho Chi Minh City.

Part of the growth in the local animation industry comes from the nature of animation itself. With shows working on anywhere from 12 frames to 24 frames (and more) per second, obviously that takes a lot of time to draw, color and animate. This also includes creating backgrounds and other effects. Over the years, this sped up as studios extended creating ‘key frames’ and sequences, then sub-contracting out the ‘filler’ frames to other people and both groups using high-end software to put it all together.

A lot of anime is static; for example a character stands still in a pose with only the mouth moving – which means there’re hundreds of smaller animations stitched together to form a whole episode. Many studios have also built libraries of special effects and sounds. Another key innovation over the years is the invention of software that can generate the in-between frames for standard movements.

This ‘stitching’ frame process becomes the bulk of the outsourcing from Korean and Japanese studios for Vietnamese animators along with creating backgrounds, often in 3D for extra effects. The end result is often as shown below.

|

|

| A gif-based example of limited animation. Note that only the mouth, eyes and arms are moving; the remainder of the image is completely static. |

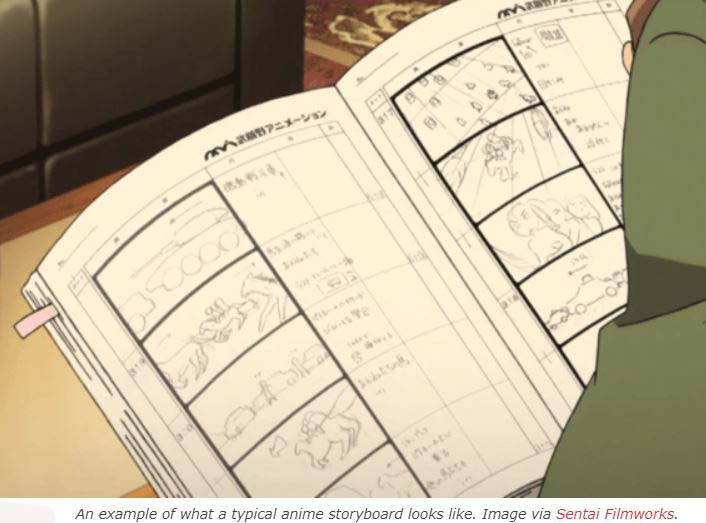

Ideas for shows and cartoons come from almost anywhere. The usual path, particularly in Japanese anime, is to buy up manga comics; manga refers mainly to the wild and wild art styles common to these comics. Other sources include in-house storyboards and scripts commissioned by production management teams.

In Vietnam, most animation companies also create short cartoon episodes and game-based entertainment. This requires the animators to work quickly over long hours. Software such as ‘Blender’, ‘Toon Boom’, ‘Maya’ and ‘Adobe Photoshop’ are standard. Because a lot of these programs work well over a network, this enables teams in different countries to work on keyframes and ‘in-betweens’ as well as checking frames and sending back artwork for corrections; called ‘tweaking’ in the industry.

Then the finished frames are put into a ‘compositing app’ which matches the frames to the backgrounds and often the audio – at this stage everything is matched with the motion and camera movements as well. Finally, it’s strung together in Premiere Pro or Adobe Media Composer for the final product along with opening and closing sequences. The music in these parts often becomes hit songs, thus generating more money for the show.

|

|

One of the greatest problems is the tension between making money and creativity and innovation. What the client imagines is often lost in translation and results in time lost revising the product and it’s hard to get the next project if you’re late with the required work. As Vu Pham from RainStorm commented, “… clients pay less but request more, their brief is kind of reasonable at first, later they keep bombarding us with changes without any extra pay …” He also noted that advertising clients were the most difficult to deal with due to budget and timetable pressure. Yet real estate companies were willing to help with details as they want the best animations of their construction projects.

|

|

As Nguyen Xuan Hien noted, “… that time the animation in Vietnam was new, so there were just a few animation companies in the country, the artwork was easy, with not much detail and not many requirements. Now, there are more animation companies, the artwork becomes more complicated, and the action is harder. With the same timework, I draw less frames. In 2013-2015, on average I drew 500-800 frames per month. But now I draw about 300 frames per month.”

The Kyoto Animation company fire that killed 30 staff overshadowed a significant detail – all the staff had a regular salary – highly unusual in the routinely outsourced animation workforce. They could spend more time on creating high-definition art and animation without the pressure of making hundreds of frames quickly. The company will recover even though it will take years and has vowed to continue this trend leading to better animation standards at a higher level.

|

|