South Korea on Thursday gave North Korea 24 hours to agree to formal talks to restart operations at their joint Kaesong industrial zone, warning of "significant measures" if Pyongyang declines.

It was a rare ultimatum from the South, which is more used to being on the receiving end of such warnings, and reflected Seoul's growing impatience with the costly impasse over Kaesong.

The Unification Ministry did not specify the measures to be taken, but there was a clear suggestion it might consider a permanent withdrawal from the zone, which normally employs 53,000 workers at 123 South Korean firms.

A rare symbol of inter-Korean cooperation, Kaesong has become the most notable victim of escalating military tensions on the Korean peninsula.

"There is no change on our stance to support the stable operation and improvement" of Kaesong, Unification Ministry Spokesman Kim Hyung-Seok said.

"But we cannot let this situation continue as it is," he added. "If North Korea rejects our proposal... we have no choice but to take significant measures."

The talks proposed by Seoul would be between the respective heads of the North and South management committees that oversee Kaesong operations.

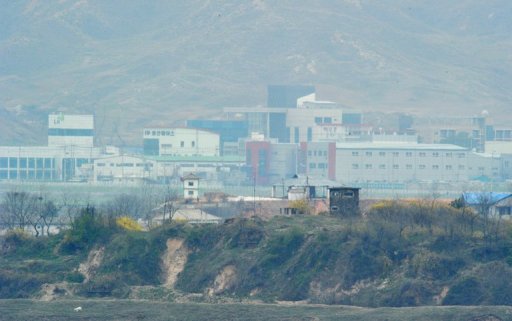

Established in 2004 and lying 10 kilometres (six miles) inside North Korea, Kaesong is a crucial hard currency source for the impoverished North, through taxes and revenues, and from its cut of the workers' wages.

The project was born out of the "Sunshine Policy" of inter-Korean conciliation initiated in the late 1990s by South Korean President Kim Dae-Jung which led to a historic summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-Il in 2000.

It operates as a collaborative economic development zone that hosts South Korean companies attracted by its source of cheap, educated, skilled labour.

Turnover in 2012 was reported at $469.5 million, with accumulated turnover since 2004 standing at $1.98 billion.

The Korean peninsula was already engulfed in a cycle of escalating tensions -- triggered by the North's nuclear test in February -- when Pyongyang decided on April 3 to block all South Korean access to Kaesong.

Angered by the South's defence minister's remarks on the existence of a "military" contingency plan to protect South Korean staff in Kaesong, the North then pulled out its entire workforce on April 9 and suspended operations.

Since then it has denied repeated requests to send food and other supplies to South Koreans who opted to remain in the zone to maintain their non-running production lines.

The association that represents the interests of the South Korean firms in Kaesong said it hoped the working-level talks would begin "as soon as possible."

In a statement, the association noted that the initial agreement establishing Kaesong committed both sides to keep the zone going for 50 years.

"Businessmen in Kaesong will not give up the right guaranteed by both governments," the statement said.

Even given the soaring tensions, the North's decision to suspend operations at Kaesong was unexpected, as neither side has allowed previous crises to significantly affect the complex.

Permanent closure would wipe out the last remaining point of contact and cooperation between North and South, which remain technically at war after the 1950-53 Korean War was concluded with a ceasefire rather than a peace treaty.

There are currently 176 South Korean staff still in Kaesong, compared with the usual number of around 850.

"The South is likely to order all remaining personnel to pull out of Kaesong," predicted Cho Bong-Hyun of the IBK Economic Research Institute in Seoul.

"Both South and North Korea are reluctant to become the first one to mention the closure of Kaesong outright in order to avoid responsibility," Cho told AFP.

Usually hundreds of South Korean managers and other workers pass through the border crossing leading to Kaesong every day.

Some have continued to show up at the border crossing on a daily basis in the unrealised hope that the North might lift the access ban.