The Vietnamese government has made a landmark decision to part with residence books and national ID cards in favor of an online database of citizens’ information retrievable with a personal identification number unique to each person.

The decision came in a government resolution signed into effect on October 30 by Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc, which seeks to streamline administrative procedures and citizens’ documents.

The resolution, based on an earlier plan submitted by the Ministry of Public Security, spells the end of Vietnam’s citizen management through permanent residence books, which ties a person to a permanent address.

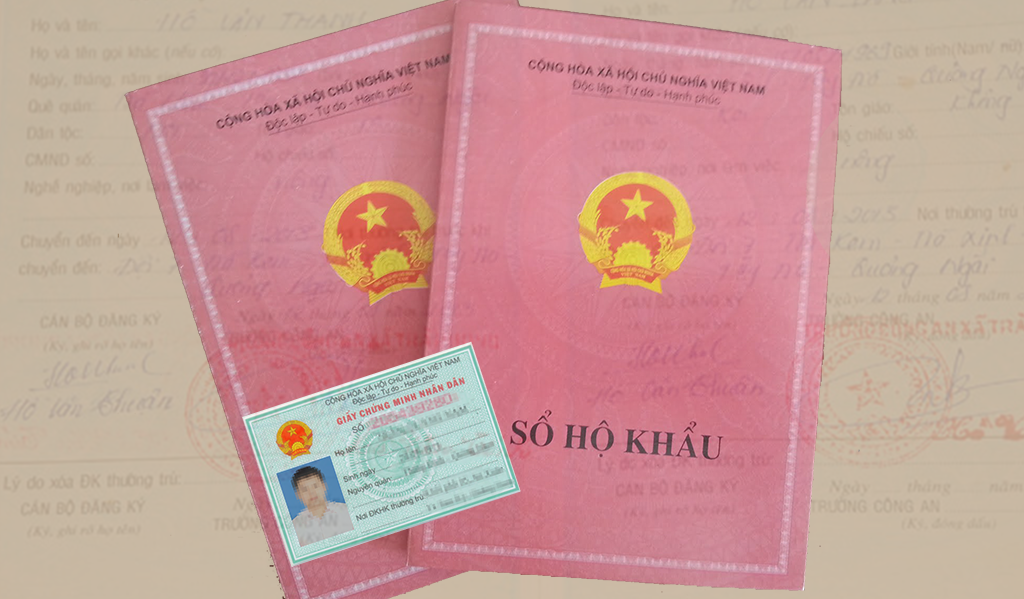

The book, ‘ho khau’ in Vietnamese, is issued to the house owner and contains information of family members who stay at the same address.

In its early days in the 1960s, ho khau was an instrument of public security, economic planning and migration control, the use of which continued after the war as a means to ration food under the then-planned economy.

In its modern form since Vietnam’s major economic reforms in the late 1980s, ho khau has been a required document when it comes to school admission, job application, registration of marriage and a range of other administrative procedures.

The archaic method of resident management has been criticized for fuelling discrimination and giving grounds to red tape, such as requiring a person living in one province to return to their hometown in another just to register for a motorbike ownership.

People without permanent residency – meaning whose names are not included in any ho khau – are also denied issuance of national ID cards, the fundamental document for every public service in Vietnam.

The government’s resolution seeks to let go of both of these physical documents and replace them with a simple, individually unique 12-digit personal identification number that is tied to each citizen from their birth.

All information regarding a person’s identity will be stored in an online database that can be accessible nationwide and updated at ease, allowing Vietnamese citizens to get access to public services by simply providing the 12-digit number instead of submitting their ho khau and personal ID card.

Such information includes a person’s full name, date and place of birth, gender, nationality, marital status, current address, and so on.

|

| Ho Chi Minh City residents register for national ID cards at a police station. Photo: Tuoi Tre |

A long-awaited decision

“It would cost the government a lot to develop the infrastructure needed to maintain good residential management after the abolishment of residence books and national ID cards, but the move would be greatly beneficial to the citizens,” said a police chief of Ngo Quyen District in northern Hai Phong City.

Nguyen Trung Hai, 37, a former registered resident of District 10, Ho Chi Minh City, said he was “moved to tears” upon learning of the news.

“I was born and raised in District 10, but has been forced to be on the move since 2005 to earn a living as a driver assistant. As I didn’t declare my absence from the permanent residence at the police station, my name was removed from the family’s residence book,” Hai recalled.

According to senior specialist Diep Van Son, the landmark resolution is a “long-awaited decision” that further signifies the Vietnamese government’s commitment to improving public services.

“I welcome the decision with extreme delight,” Son said.

Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter to get the latest news about Vietnam!