The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that up to 90 percent of Asian high school children, including Vietnamese, are currently suffering from nearsightedness.

Decreased exposure to outdoor light and spending too much time studying indoors appear to be a major factor in rising rates of myopia, or nearsightedness, in young people around the world.

People with myopia can see close-up objects clearly, like the words on a page, while their distance vision is blurry, and correction with glasses or contact lenses is likely to be needed for activities like seeing the blackboard clearly, cycling, driving, or recognizing faces down the block.

The growing incidence of myopia is related to changes in children’s behavior, especially how little time they spend outdoors, often staring at screens indoors instead of enjoying activities illuminated by daylight.

The devastating pandemic of COVID-19 in 2020-22 may be making matters worse, the New York Times reported, citing the WHO.

Susceptibility to myopia is determined by genetics and the environment.

Children with one or both nearsighted parents are more likely to become myopic.

However, while genes take many centuries to change, the prevalence of myopia in the United States increased from 25 percent in the early 1970s to nearly 42 percent just three decades later.

The rise in myopia is also not limited to highly developed countries as the WHO estimates 80 percent to 90 percent of high school children in East and Southeast Asia are now myopic.

The organization projected that half the world’s population may be myopic by 2050.

Given that genes do not change quickly, environmental factors, especially children’s decreased exposure to outdoor light, are the likely cause of this rise in myopia, experts believe.

|

|

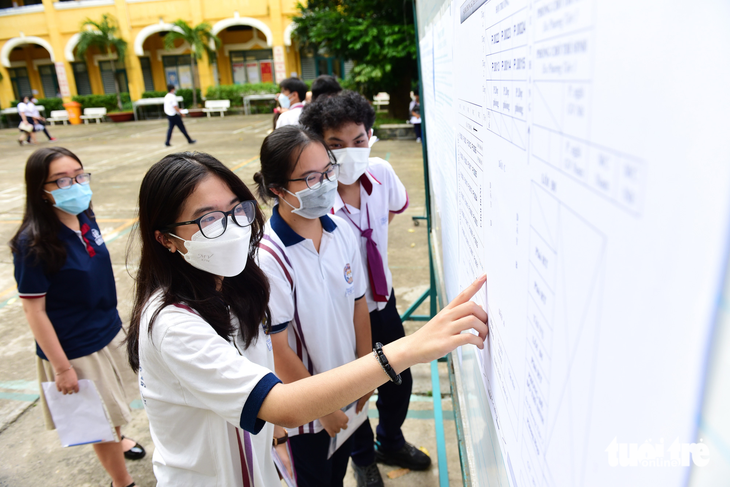

| Children wearing glasses read textbooks at school in Vietnam. Photo: Nhu Hung / Tuoi Tre |

The factors that keep modern children indoors may include an emphasis on academic studies and their accompanying homework, the irresistible attraction of electronic devices, and safety concerns that demand adult supervision during outdoor play.

All of these things drastically limit the time youngsters now spend outside in daylight, resulting in the likely detriment of the clarity of their distance vision.

Recent researches read by the New York Times suggested that months of COVID-induced confinement may be hastening myopia’s silent progression among young children.

Particularly, a Canadian study that examined children’s physical activity, outdoor time, screen time, and social media use during the COVID-19 lockdown in early 2020 found that eight-year-olds spent an average of more than five hours a day on screens for leisure, in addition to screen time needed for schoolwork.

Researchers from Emory University in Atlanta, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Tianjin Medical University Eye Hospital in Tianjin, China, described a substantial decline in the visual acuity among 123,535 elementary school children following school closures in 2020 from January until June.

Compared to the results of previous annual screenings, the ability to see distant objects clearly had fallen precipitously, especially among those ages six to eight.

The children became far more myopic than expected, based on changes in acuity that were measured at the start of the school years 2015 through 2019.

But a similarly dramatic drop in acuity among older children was not found.

Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter to get the latest news about Vietnam!