Former Australian Ambassador Graham Alliband shared stories from the five decades he has spent working and falling in love with Vietnam in an exclusive interview with Tuoi Tre (Youth) newspaper.

The interview was given shortly after Alliband was conferred an honorary doctorate from Thai Nguyen University on June 21 for his contributions to the university.

Alliband’s diplomatic career in Vietnam began in January 1972 when he served as the Third Secretary of the Australian Embassy in Saigon.

He then went on to spend seven years working as the director of an Australian non-governmental organization before being appointed Australian Ambassador to Vietnam for a three-year term in 1988.

After his ambassadorship ended, Alliband directed four different development programs sponsored by the Australian government in Vietnam from 1997 to 2018.

The former ambassador spoke to Tuoi Tre in his personal capacity and not on behalf of the Australian government.

The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Congratulations on being awarded an honorary doctorate from a leading Vietnamese university. You have devoted most of your life to Vietnam. Can you briefly highlight the fundamental changes that Vietnam has experienced since you first arrived in 1972?

I have witnessed extraordinary changes over the 47 years since I first set foot in Vietnam in January 1972 as a young diplomat at the Australian Embassy in Saigon. In 1972, the war was still raging and I could hear the bombs being dropped by American planes in provinces surrounding Saigon.

I saw first-hand the destroyed villages and visited camps of dislodged villagers fleeing the war.

In mid-1973 Australia opened an embassy in Hanoi. In January 1978 I was posted as First Secretary to the Australian Embassy in Hanoi.

In January 1981, I resigned from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs after ten years as a diplomat and became director of an Australian NGO focused on overseas aid projects. That position brought me to Vietnam for a third time.

In the first half of 1980, I made two trips to Hanoi which resulted in the Australian NGO providing the first milking machines to Moc Chau dairy farm [in the namesake northern province], medical supplies to Thanh Tri Hospital in Hanoi, and artificial insemination equipment to the Ba Vi cattle farm [in the Vietnamese capital].

|

|

| Australian Ambassador to Vietnam Graham Alliband is pictured during a trip to deliver food aid in northern Vietnam in this supplied file photo. |

You served as Australian Ambassador to Vietnam from 1988 to 1991 while our country was in the midst of the Doi Moi (Reform) movement that began in 1986. What are you most impressive and unforgettable memories during this special diplomatic term?

My next encounter with Vietnam was much more satisfying. At 43 years old, in August 1988, I was appointed to a three-year term as Australian Ambassador.

Doi Moi brought new vigor to Vietnam and the country began to change in many ways. The most significant change was probably the policy reversal which legalized private enterprises. The most obvious symbols of the rebirth of private enterprise were the restaurants and coffee shops which opened in Hanoi and the appearance of the first few privately-owned vehicles on the capital’s roads.

The economic policy changes since Doi Moi have been truly revolutionary and are the root of Vietnam’s very dynamic and rapidly growing, booming economy today. I recently witnessed the extraordinary changes that are taking place throughout the country during a month-long road trip from Hanoi to the [southernmost province of Ca Mau]. The contrast between this trip and the first road trip I took from Saigon to Da Lat in 1990 is huge.

As the Australian Ambassador in Vietnam during a very difficult time highlighted by the U.S. embargos against Vietnam and the collapse of the Eastern European bloc, you helped make several contributions to the changes in the Vietnamese government’s policies toward Australia and the West. Please highlight a few achievements that you are particularly proud of?

During my posting as Ambassador, while Vietnam’s economic market reforms were being introduced, Vietnam began reaching out to countries in the West. This move was accelerated after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990. As one of a handful of Western countries with embassies in Hanoi, Australia was ready to assist Vietnam in expanding its external relations and ending its diplomatic isolation from the West, even in the face of opposition from Australia’s close ally the U.S., as well as Singapore.

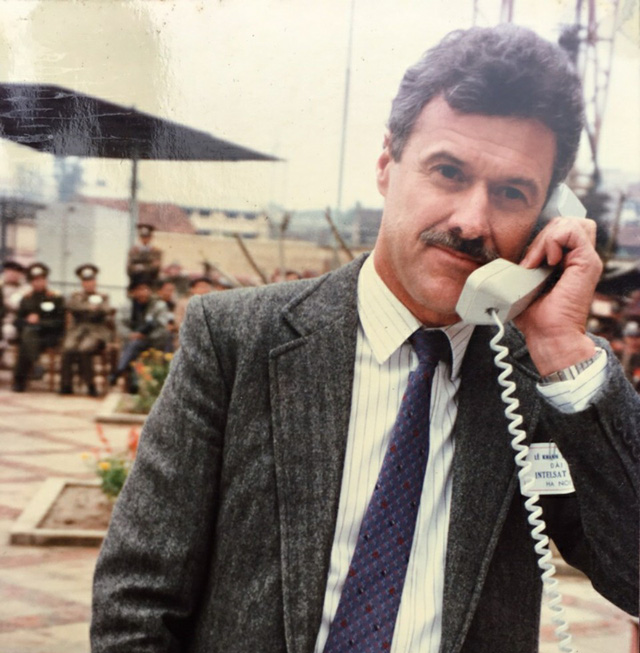

One thing that I am proud of is the first telephone call I made from Ho Chi Minh City to Australia via the new international telecommunication links through the INTELSTAT satellite system, which was installed by the Australian company OTCI.

Vietnam’s direct links with the INTELSTAT system was a symbol of the country’s entry into the international community and the end of its complete dependence on the Soviet Union. Previously all international telephone calls had to be routed via Moscow with a waiting time of five to six hours!

Regarding Vietnam’s current education system, which areas do you think the country should focus on most in order to improve?

Vietnam has made considerable strides in reforming its education system over the past few years in order to bring the country in line with international standards.

What’s particularly noticeable is the recent effort by Vietnam’s government to improve the vocational educational system so that graduates can meet the labor needs of the private sector.

One weakness of Vietnam’s educational system is the lack of research being undertaken at universities. This weakness has been recognized by Vietnamese authorities and new regulations have been introduced to grant more incentives and requirements for research at universities and push a number towards becoming ‘research universities’. Under the current push towards university autonomy, universities will be able to determine their lecturers’ salaries and the resulting increase in salaries should include incentives for academics to do more research.

|

|

| Australian Ambassador to Vietnam Graham Alliband makes an international phone call to Australia in this supplied file photo. |

Studying overseas has become very popular amongst Vietnamese youth; however, in your view, how “capable” are Vietnamese students after they return from studying abroad? What skills do Vietnamese students need most to market themselves to companies?

There are around 25,000 Vietnamese students studying in Australia at any one time, the vast majority of whom are privately-funded and a very large portion of them are studying English. Clearly the acquisition of the English language alone is going to be of benefit when these students return home because Vietnam is integrating quite intensively into the international community. For many of those who undertake studies of two years or more, the study and living experience in Australia, especially those on Australia Awards Scholarships, leads to significant changes in their way of thinking and their approach to work and life when they return.

What are the positives and negatives of the regulations authorities have enacted to conserve and develop Vietnam’s heritage sites, such as Ha Long Bay and the former capital of Hue?

Preserving this rich heritage is a challenge due to the difficulties in striking a balance between conserving what is unique and beautiful and meeting the legitimate requirements of local and international tourism.

As someone who has visited Ha Long over 100 times to enjoy its unique natural beauty, I am honestly disappointed by the scale and nature of development on Ha Long Bay’s shores, especially the erection of the huge cable car system and Ferris wheel on a nearby mountain top.

In contrast, the conservation of the historical structures and buildings in Hue, which I just recently visited, is impressive. The restoration work in the citadel and in the tombs of former emperors has been executed with the highest quality of workmanship and with genuine care. The way tourists at these sites are handled is very systematic and appropriate.

In my view, there needs to be a strong national authority overseeing all developments which impinge on the natural beauty of unique geographic and man-made historical locations, so that commercial considerations are not allowed to spoil the value and special qualities of heritages that must be preserved for the Vietnamese people and mankind as a whole. Unfortunately, at some heritage sites, it may be too late.

|

|

| Former Australian Ambassador to Vietnam Graham Alliband is pictured in Hanoi in July 2019. Photo: Nam Tran / Tuoi Tre |

You are very well known for being highly appreciative of Vietnamese cultural and traditional values. What can the country and its people do to maintain such values?

Vietnam has been able to largely preserve its cultural and social traditions despite a succession of foreign interventions. I have witnessed a cultural reinvigoration over the last two decades, evidenced by the resurgence of village and religious festivals, as well as a wave of new construction and the repair of pagodas, temples and churches.

A key aspect of the Vietnamese value system is the focus on extended families and the importance of various celebrations and ceremonies. Vietnam has a good model in Japan, a country that has remarkably preserved much of its social and cultural values despite its highly developed economy.

What to avoid? Probably the most pernicious influence from the West and other developed countries that Vietnam should try to avoid is the rampant consumerism and the value placed on material things at the expense of spiritual and human values. Unfortunately, there are some negative signs of consumer exhibitionism showing up in Vietnam with the appearance of luxury cars, such as Rolls Royces and Ferraris, on the streets of Hanoi.