Photographer Lam Duc Hien of World Press Photo Contest fame sat down with Tuoi Tre (Youth) newspaper during his time at the 2022 Hue Festival to reflect on the portraits that made his name, the life-or-death experiences, and the state of modern photojournalism after spending three decades in the ever-changing industry.

How did you get your start in photography?

At the beginning, I did not even plan to do photography professionally. It started when I joined a non-governmental organization (NGO) because I want to help people. I went to Romania with them in 1990 and they asked me to take pictures. [In 1990, the country was experiencing perpetual social unrest and political battles following the Romanian Revolution in December 1989].

The pictures were used in campaigns to raise money for Romanian children, and after that, the NGO said they got a lot of donations. It made me understand the power of a picture - a good one can help mobilize a lot of money. They [the NGO] then asked me to work for them, but I was still in art school at the time, so I only went on missions with them as a volunteer during holidays. The pay was low but I didn’t care, because I didn’t need money at the time. I got to stay at friends' houses and was traveling everywhere, and because of that, I felt like I was very rich.

|

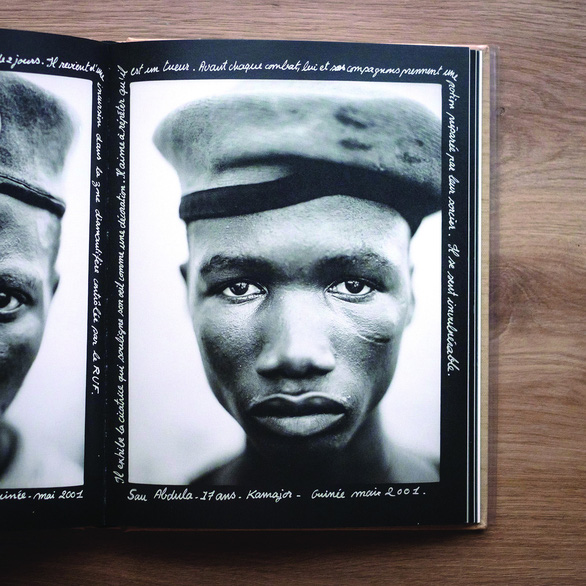

| A 17-year-old boy from Sierra Leone, photographed in a refugee camp in Guinea in May 2001. Excerpt from Lam Duc Hien’s ‘Faces’ photobook. Photo: Le Xuan Phong / Matca |

You also spent time working as the head of a mission for an NGO, is that correct?

Yes, I was the head of a mission in Iraq. I organized work for doctors and nurses who came from France. We also distributed food for children in school. When I returned 20 - 25 years later, I could still feel the gratitude from the people I helped. You never know - people you helped can become like a farmer or a president - after 30 years. [Several Kurdish fighters photographed by Lam Duc Hien in 1990 later became political figures, assuming the roles of president and vice-president of Iraq’s Kurdistan autonomous region].

I think I was the only foreigner photographer in Iraq after 1991. I was in Baghdad, traveling south to Basra, everywhere. [I was able to do that] because I know how to make good contact with people, and also because of my Asian physique.

When you say to the Saddam Hussein [regime] authority that you are Vietnamese, it’s like “You’re brave people who won the war against America.” They give me a visa every time. However, it's still not easy: During Saddam times, you always have the Secret Service following and keeping an eye on you. At the time, they had just caught an English journalist and hung him after accusing him of being a spy, so I had to be very careful when taking pictures as well.

I think your “Iraqi” series that won the World Press Photo Contest 2001 for Portraits was also shot during this time?

Correct. After 1991, they [the United Nations Security Council] imposed an embargo on Iraq, and it was really hard for the Iraqi people. You cannot import things like graphite or chlorine [for water filtration] because they could also be used for nuclear bombs, so the people were dying from diarrhea.

I was against the embargo, and I took pictures of local people to show the consequences of it. My agency (Agence VU) tried to get these pictures out, but nobody cared. I was fatigued, so in my next work, I did not want to show any context - just the sadness in the face of survivors. I took one portrait and repeated it after one or two years, and I started to realize how their condition worsened in the picture.

I didn’t think they were photojournalism, but my agency convinced me to submit them to World Press Photo - then I got the first prize for Portraits. After that, the press and the people became interested. The biggest newspaper in France published it - double page - and sent me back to Iraq - with money and everything - to cover the conflict.

A journalist once asked me why I did the ‘Iraqis’ project, and I said “Because I have a big ego.” I kept doing it because in each pair of eyes of the people, I see myself. When I take these pictures, I feel like I’m picturing myself. I see my family, my mother, and my sisters. I take pictures of them the same way I wanted people to photograph me when I was a refugee - with a lot of respect and humility.

|

| A young girl living in Baghdad. Part of the ‘Iraqi’ series, 1st prize winner in Portraits at the World Press Photo Contest 2021. Photo: Lan Duc Hien / Agence VU |

You have an education background in arts, but then decided to pursue photojournalism. Do you think there is a clear distinction between the two disciplines?

They are not so different for me. When I first worked in an NGO, they asked me for pictures that could be used for the press, but I did not want to make documentary pictures - I wanted to put my personality onto the photos. I don’t really care about subjectivity or objectivity.

I was lucky to find Agency VU. The director at the time (Christian Cajouelle) liked to recruit photographers with personalities. I came to this agency because they don’t care if you work with the press, galleries or anything - you are a photographer first, not a journalist or an artist, and your photography should be able to convey ideas before anything.

Do you consider yourself a war photographer?

No, I'm not a war photographer. War photographers are a little bit obsessed with violence, and I’m not. When you leave your country because of the violence of a war, and then you face domestic violence in your family, you know how terrible it is.

I once had an assignment for an NGO where I covered violence against women in the war zones of Africa and South America. In Africa, rape was sometimes used as a weapon, and some female victims contracted AIDS. They have no self confidence; they don’t even want to show their face. Some other photographers spent only five days with them, but I stated that I needed three weeks. I spent time with the social workers before visiting the women, and only then did I take pictures. I printed out the best shots and showed it to the subjects; they appreciated it, saying “He looks at me as a woman, not an animal or non-human,” and accepted my presence.

I think that’s part of your photographic process: Approaching the subjects, then making them forget about our existence.

Exactly, I call that “làm quen” (get to know) and “làm quên” (make one forgets.) When I take pictures, I need to be invisible. It can take me hours to take one photo if the subjects can’t forget about me. Because I don't always have time, I have to find out another way, such as asking people to pose for the portraits. Sometimes, it looks like the photo takes one second to make, but there’s still a lot of work behind it. It’s the genius of the artist, and it comes from working hard, not a gift from God.

You have pursued photography for a long while, and have just got done teaching a photo camp in Hue City. Do you plan to become a photography professor in the future?

No, I don’t think so. It's good to pass on your passion, but I feel a little bit ashamed to teach photography today, because there's barely any jobs for photographers - the market is very bad. If you want to earn money, don't do photography - that's what I say to them. People pay a lot of money to attend photography workshops in Europe, not to mention travel costs to make reports in another country. It’s like a passion project, and only rich people can do it.

I know that you have many many places to call home. How would you describe your relationship to Vietnam?

I think it's related to my grandmother. When I was living with my grandmother as a kid, I got to sleep next to her. She breastfed me to help me stop crying - even though she cannot lactate anymore. She cooked and bought food for me throughout my childhood. I have always remembered those things growing up, so when I come to Vietnam, I instantly feel like I'm home. But I also think about myself as an exile, traumatized by the war. I don't have a fixed home; I’m always on the go. But after all, I take it like: “It made me resilient because I can live anywhere.” Home is not a place - I bring it with me in my heart and mind. With my suitcase, my camera, I can go anywhere.

Lam Duc Hien (1966) was born on the shores of the Mekong River in Paksé, southern Laos. He arrived in France in 1977 after spending two years in a refugee camp in Thailand.

He has testified to the consequences of the 20th and 21st century’s major conflicts on civilians around the world, including in Romania, Russia, Bosnia, Chechnya, Rwanda, South Sudan, and above all in Iraq, which he has covered for over 25 years.

Hien has won numerous awards, including the Leica Prize, the Great European Award of the city of Vevey, and the World Press Photo, among others.

Like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter to get the latest news about Vietnam!